Panama Canal Cruise

Mike and Judy Henderson

April 11 to April 27, 2016

The transit of the Panama Canal is the highlight of this cruise so I'll include more pictures and text about it than about some of our port calls.

Rather than try to give you the history of the building of the canal, I'll refer you to this article in Wikipedia. It does a good job of summarizing the story in a page or two. If you're looking for more, you can read "The Path Between the Seas" by David McCullough. No detail is too small or insignificant to be omitted from his book - it's a real snoozer, especially the part about the French attempt to build the Canal.

The canal opened in 1914, so it's over a hundred years old now.

Here's a map of the canal showing the location of the locks. I hope it will give some perspective to our photos so you can visualize where we are in the various pictures. The canal runs mostly north and south and that's the directions spoken of for ships traversing the canal - northbound or southbound. Where there are double locks (locks side-by-side) they are spoken of as east locks or west locks.

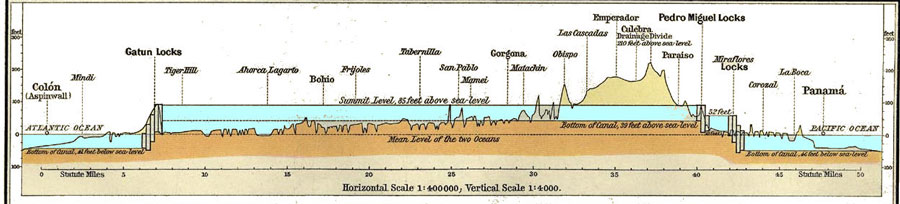

I've included this next map to give you some idea of the cross section of the canal, especially how the locks work to raise and lower ships during the transit. One interesting question is "Why are there three locks on each side? Why not just one? Or four or five?" I don't want to take time to discuss that here, but I'll put an appendix to this page that discusses this question for those who are interested - and those who aren't can skip it.

Judy and I set our alarm for 6am and when it went off, we were passing by the small islands on the Pacific side of the entrance to the canal. That's Panama City in the background - lots of high rise buildings.

Soon the pilot boat was approaching us. This pilot will board our ship and take us through the first three locks, then leave the ship. When we approach the Gatun locks, another pilot will join us to take us through those locks.

The first "landmark" we came to is the "Bridge of the Americas". The bridge was built in 1962, but is one of the limiting factors to ships getting through the canal, especially now that the new locks are being built to accommodate larger ships (see Panama Canal Expansion). Clearance is about 200 feet and some of the larger ships, especially container ships, that will fit into the new locks cannot get under the bridge. The Centennial Bridge was built in 2004 to replace this bridge but the Bridge of the Americas is still being used. The Centennial Bridge is 15km north of the Bridge of the Americas.

A little later, we reached the first locks, the Miraflores locks. This set of locks contains two chambers and will lift us to 54 feet above sea level to Miraflores Lake. Then we will sail across Miraflores Lake to the Pedro Miguel locks which will lift us about 31 feet to the level of Gatun Lake, which is nominally at 85 feet above sea level.

Here we are approaching the first chamber of the Miraflores Locks. We're using the east side locks.

Small locomotives, called "Mules", are hooked to the ship to help guide us into the lock chamber. The mules don't pull us into the chamber, they only keep us centered in the chamber. There's about two feet of clearance on each side of the ship.

When the gates opened to the first chamber, at sea level, we began to enter. You can see the gate opening in the picture below. Note how the sides of the chamber have dark algae growth up to the level of the water when the chamber is filled.

The pilot pulled up right up to the gates. I thought for a moment he wasn't going to stop but he did just in time. I guess he's done this a few times before:-) Note the water level in the second chamber - that chamber is completely full, right up to the edges of the chamber.

And here's a picture of the side of the control tower.

The water from the second chamber is then drained via gravity into the first chamber and we began to rise. The gates, which are very visible in the picture above, are beginning to disappear beneath our bow. Note that you can see the sides of the second chamber as the water is drained to the first chamber. When the levels equalize, they will open the gates and we'll proceed to the second chamber.

There's a sea bird perched on the gate, totally unconcerned.

Now, the water levels have equalized and they're opening the gates for us to proceed to the second chamber. You can see one of the gates opening in the lower right of this picture.

Here we are approaching the gates of the second chamber, where we will repeat the process to be lifted to the level of the lake. It's like a giant aquatic elevator.

A view of Miraflores Lake, which we will cross to reach the Pedro Miguel lock.

As we were leaving the lock, another cruise ship was arriving at the Miraflores Locks. Since I can't take a picture of our ship entering the locks, this picture shows what it looks like when a cruise ship approaches the locks.

Looking back as we depart the Miraflores locks, you can see the lock gates begin to close in preparation for the next ship.

Fairly quickly we reached the Pedro Miguel locks. This time we were using the west locks.

Transiting this lock was exactly the same as the Miraflores locks so I won't bore you with a lot of details. Leaving the Pedro Miguel locks, we entered the Culebra cut. This was the most challenging part of the building of the Panama Canal. It was the highest part of the isthmus and it broke the back of the Continental Divide.

At the end of the Culebra cut, we came to Gamboa and found this giant floating crane. It was a war spoil that was shipped from Germany via the Magellan Strait to the Long Beach Naval Shipyard on Terminal Island where it was used for many years. It was recently given to Panama and it is now used to lift the gates of the Gatun Dam when they need repairs. Here it's called Titan, but in Long Beach it was referred to as "Herman the German." (another link here.)

Gamboa marks the beginning of Gatun Lake, which is fed by the Chagres River.

After sailing across Gatun Lake, we come to the Gatun Locks. Gatun Lake was created by the building of the Gatun Dam across the Charges River. Here are the gates of Gatun Dam, fairly close to the locks. About this time, rain clouds were starting to roll in and we had a few quick rain showers. I've PhotoShopped the pictures to brighten them.

Here are the Gatun Locks, with a larger container ship entering the first chamber of the west locks. At the Miraflores locks I described our transit through the locks, but you couldn't see our ship in the locks. Here I'll be able to show pictures of a large ship transiting the locks.

Here, the container ship is just about completely in the first chamber.

And the gates are closing behind her.

Now, the gates are opening for us. You can see the ship ahead of us in our lane, which appears to be in the third chamber now.

By now, the container ship has been lowered in the first chamber and is ready to enter the second.

We're entering the first chamber and the ship ahead of us is departing the third chamber.

Just downstream from the Gatun Locks they're building a new automotive bridge. This may be the bridge, completed in 2019.

In the meantime they use a ferry to carry automobile traffic across the canal.

And then we clear the breakwater of Limon Bay, enter the Caribbean, and go on to Curaçao.

The final part of our trip is here.

Appendix - Why are there three locks on each end of the Panama Canal?

The level of Gatun Lake is approximately 85 feet above sea level, and ships are raised and lowered to/from this level through three chambers on each end of the Panama Canal. But why three? Why not one? Or four or five?

The Bollene Lock on the Rhone River in France has a 75 foot lift (see picture below). Why not do that on the Panama Canal?

The answer is a trade off between time and water usage.

The Panama Canal locks are 1,000 feet long and 110 feet wide. The amount of water necessary to raise the level of the water in the lock by one foot is 110,000 cubic feet of water. One cubic foot of water is 7.48052 gallons, so this equates to 822,857 gallons. To make things simpler to talk about, let's call this amount of water "one lock-foot".

If one lock is used to raise or lower a ship, 85 lock-feet of water will be used because the ship must be raised or lowered 85 feet.

Suppose three chambers are used and each raises or lowers the ship by the same amount. Each chamber will raise or lower the ship by 28.3 feet so 28.3 lock-feet of water is required for each chamber. But the water for each of the two lower chambers comes from the next higher chamber.

Let's look at a ship descending. It will enter the upper lock, and 28.3 lock-feet of water will be drained to the next lower lock. Then the ship will enter the middle lock, and 28.3 lock-feet of water will be drained from the middle chamber to the lower chamber. Then the ship will enter the lower chamber and 28.3 lock-feet of water will be discharged to the ocean.

So the ship only used 28.3 lock-feet of water to transit the three chambers of the locks.

So why not use five chambers? That way, only 17 lock-feet of water would be used. But it would take the ship more time to transit five locks than three, and it would cost more to build five chambers than to build three chambers.

So three chambers is a compromise between the amount of water used to transit a ship and the time required to complete the transit.

[Added note] Water usage is important to the Panama Canal. Panama has a wet season and a dry season. To help store water for Gatun Lake, the Chagres River was dammed upstream to create Madden Lake (now Lake Alajuela) During the dry season, water is released from Madden Lake to keep the level of Gatun Lake at 85 feet above sea level.

This year Panama has been experiencing drought conditions. Madden Lake has already been drained so there's no more reserve of water. The level of Gatun Lake has fallen to the point that the canal authority has had to reduce the limit for ship draft. If a container ship arrives with draft that exceeds the allowed limit, they can offload some of the containers, ship them across the isthmus by train, then reload them on the other side.

Here's a news article from 2015 about the drought conditions and its effect on the Panama Canal.

The final part of our trip is here.